iPad/Tablet Users: Please rotate your device horizontally to experience the story.

Phone Users: This story is not designed for phone screens, and is best viewed on a larger screen/device.

Thank you!

BACK TO HOME

Click "View Item in Archive" to open it in a new browser window

and progress bar

Click pullouts to read more indepth information

The

Memorial Day

Massacre

A story told through Museum objects saved by Southeast Chicago residents

BEGIN

View story items from the archive

and open in a new browser window

“My mom kept a good book... All my family was here: my mom, my dad, my uncles. Because they wanted to form a union. Back in them days, they had no rights as workers.”

- Mike Borozan

Son of Gerry Jolly Borozan

Before the Massacre

Captain James L. Mooney

Red-baiting

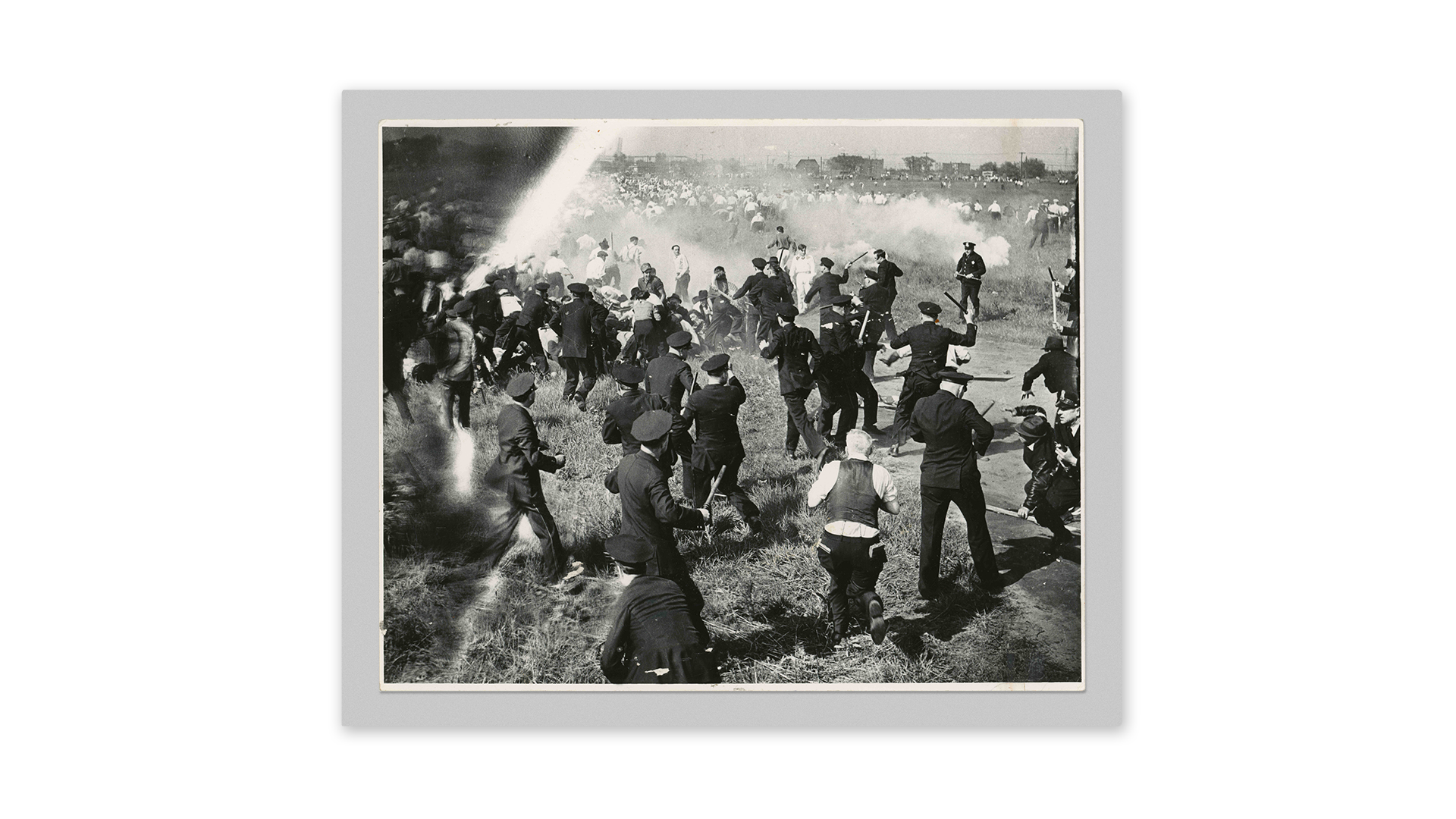

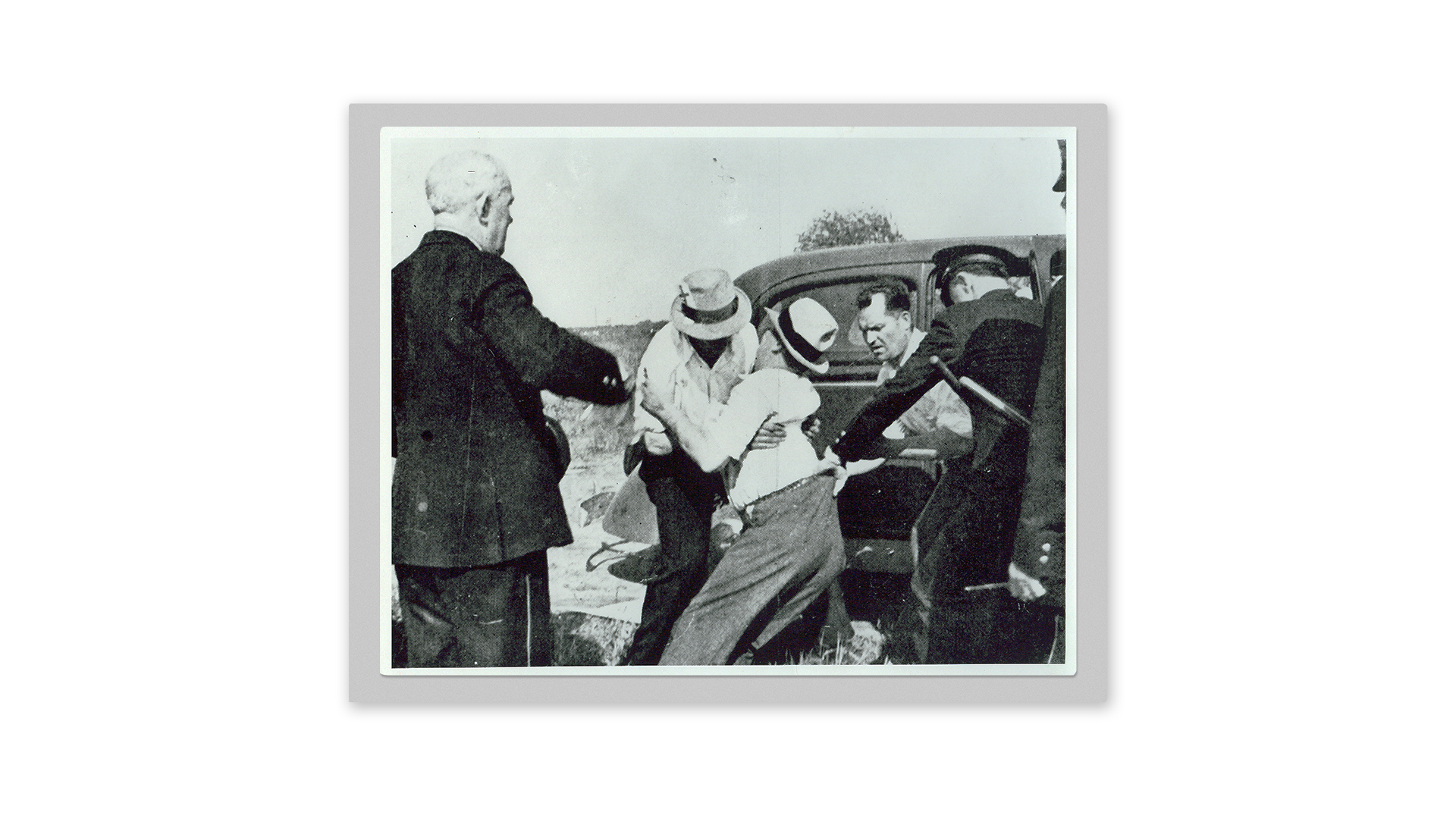

The Massacre

Content Warning:

The following section contains images of violence inappropriate for younger viewers

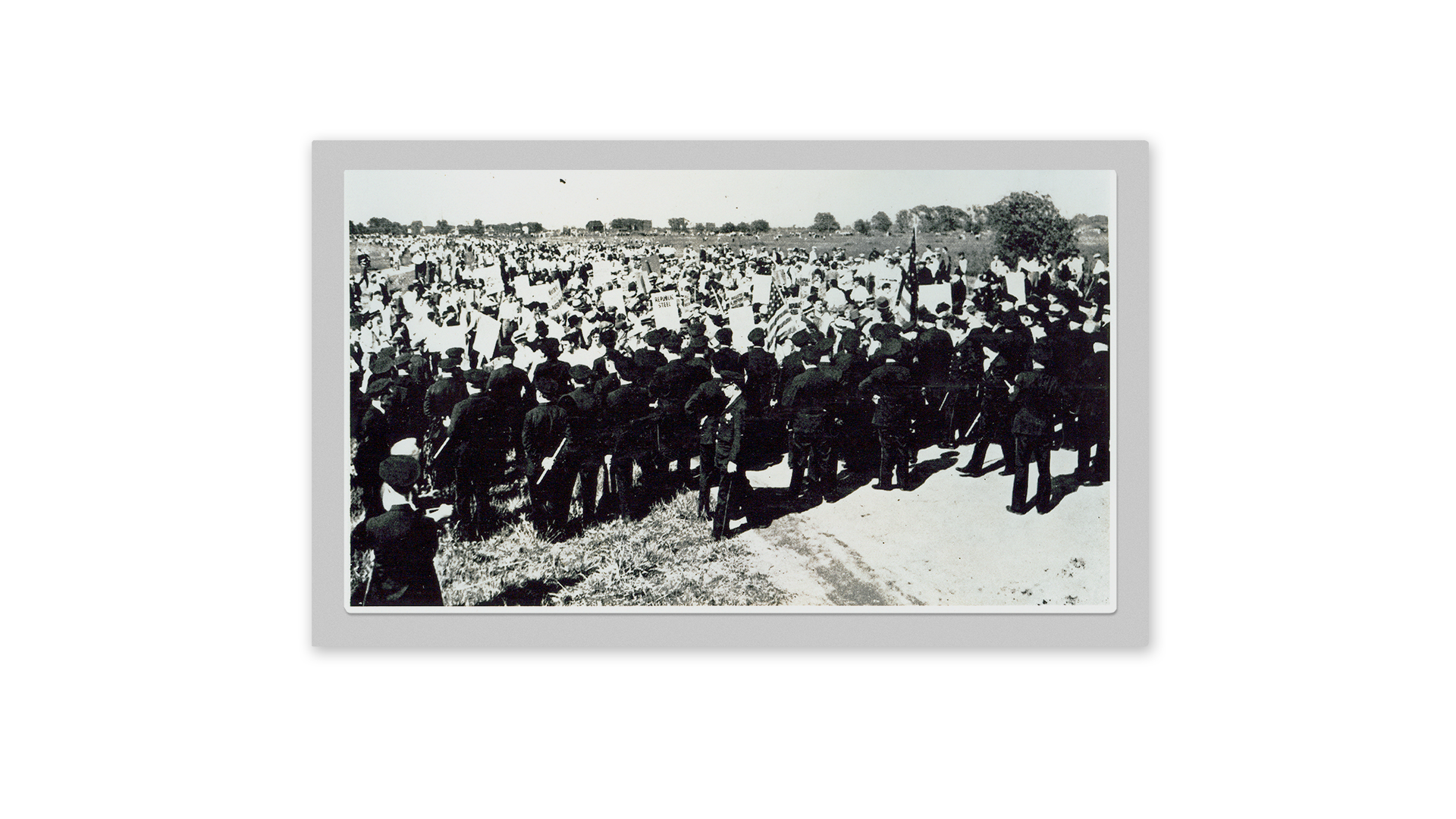

The rally would take place in the field next to Sam’s Place, just outside the Republic Steel gates.

Large numbers turned out for the rally. Neighbors and family members arrived along with supporters from other parts of Chicago. Strikers from the “Little Steel” mills across the Indiana border also came in a show of solidarity.

“That was a gorgeous day. It was beautiful, it was warm and there were thousands of people there. They brought their kids and picnic baskets. We were singing songs and yelling our slogans. I had already learned a lot of these union songs, so I was actually leading the singing. I got up on the podium... ‘C‑I‑O.’ Everybody was in a great mood.”

Mollie West

Chicago labor activist

“They would all march through that big prairie. I lived in the second house right from where we were standing in that prairie. They wanted to get through so they could walk in front of the main gate of the Republic Steel. The Wagner Act says you can walk.”

Gerry Borozan

East Side Resident

“I watched the Paramount Newsreel fellows set up their newsreel cameras on the truck. And I listened to some of the police talking to themselves saying, ‘Let those bastards come down here, and we’ll take care of them when they come down.’”

Sam Evett

SWOC organizer

“I was right up there in front as we marched through the prairie. It was a peaceful march. But we were stopped by a line of police officers just stretched across from one side of the road to the other.”

Gerry Borozan

East Side Resident

“I walked right between the lines. You can see how nervous I am. I’m biting my lips as I go along, you know?”

George Patterson

local union leader and SWOC organizer

The newsreel cameraman paused to change his lens.

Then he quickly started rolling again...

RETURN TO FOOTAGE WITH SPEED CONTROLS

“I see the guys falling like wheat to my right. Those are the ones that got killed, they got shot.”

George Patterson

local union leader and SWOC organizer

“I looked around, and I really, for the first time in my life, saw a battlefield, because that’s what it looked like. It was a battlefield. I was right on the ground, and there were maybe five, six people on top of me. But it was that that saved me from also being hit.”

Mollie West

Chicago labor activist

“Everybody started running back. Everybody was frightened, but I ran right home because I lived right there. And my boyfriend, Steve, and brother Jim, they were in the crowd, and they were running back.”

Gerry Borozan

East Side resident

“People were just dragging bodies towards Sam’s Place. There was a policeman pointing a gun in my back and saying, ‘Get off the field or I’ll put a bullet through your back.’ It was just a horrendous, absolutely horrendous sight. There was one father, who carried his kid, and one of the bullets hit the child’s foot and shot off the heel of his foot.”

Mollie West

Chicago labor activist

... a patrol wagon drove in... and it stopped right in front of us... I had one foot on the step when a policeman put his hand on my back, on my buttocks, and shoved me in there...

I started helping these men who were in the wagon... and I noticed that there was one particular fellow there who looked very gaunt and haggard, and he seemed to be in a terrible position. There was a heavy-set man that had fallen on top of him, and this fellow was pinned completely with his head over his knees. I straightened him out, managed to get his head on my lap, but when I did that I noticed that his face was getting cold and was turning black, and he was motioning to his shirt pocket...

He had a package of cigarettes there, and I understood he wanted me to light a cigarette for him... and when I did get the cigarette out it was cloaked with blood, so he said, “Never mind, kid” he says, “You’re all right…” And he started to say “mother” but didn’t finish, and he stiffened up, and I became somewhat hysterical.

I told the policeman that was in the back of the wagon... I said, “Your children and wife must be very proud of you.” And he says, “I didn’t do that,” he says “I wouldn’t do that.”... And as he said that I noticed the tears rolling down his eyes.

pgs. 4951-4952 La Follette Committee Report

After The Massacre

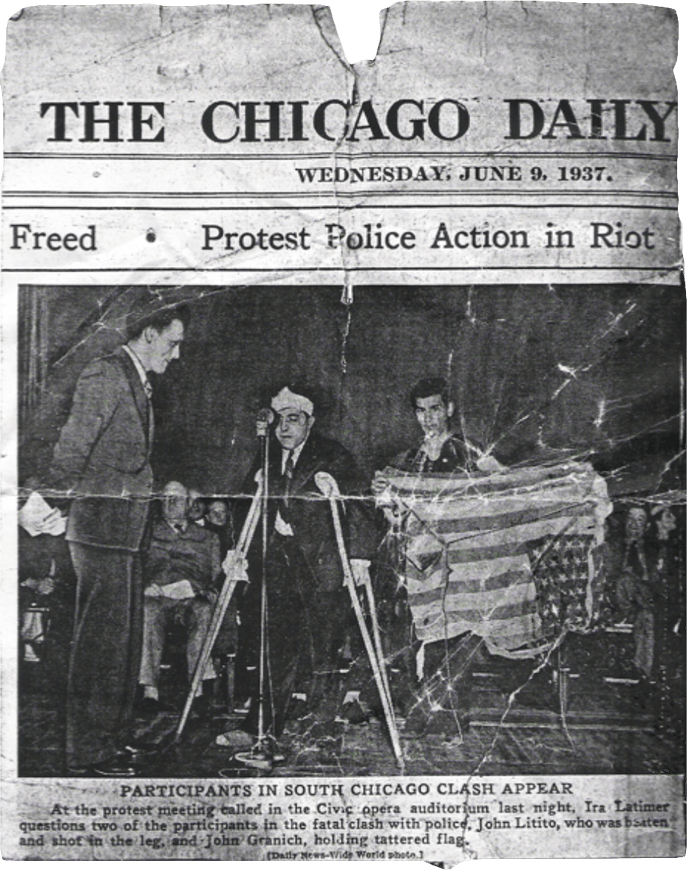

Striker John Lotito, a flag-bearer shot in the leg, speaks at Civic Opera House protest meeting. Clipping donated by his son, John Lotito, Jr.

Remembering the Massacre

“American Tragedy” by Phillip Evergood, 1937

“Current News” by Bernece Berkamn-Hunter, 1937

“Citizens” by Meyer Levin, 1940

Kathleen Peebles remembering the dead

70th Commemoration, 2007

Gerry Jolly Borozan, 60th Anniversary Commemoration (1997)

“Thanks guys for getting things going for us... they need the unions.”

- Mike Borozan

Son of Gerry Jolly Borozan

PRODUCED BY: Chris Walley, Chris Boebel

CREATIVE DIRECTOR & UI/UX DESIGNER: Jeff Soyk

STORY NARRATIVE: Chris Boebel, Chris Walley, Jeff Soyk

PROJECT MANAGERS: Chris Walley, Jeff Soyk

RESEARCH: Chris Walley, Rod Sellers

PROJECT ARCHIVIST: Derek Potts

FRONT-END DEVELOPER: Jeff Soyk

OPENING AND CLOSING VIDEOS: Chris Boebel

VIDEO EDITING: Paige Mazurek, Chris Boebel

UI/UX DESIGN SUPPORT: Paige Mazurek

SOUND DESIGN: Billy Wirasnik, Chris Boebel

STUDENT ASSISTANTS: Jocelyn Yu, Anna Vold

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: Thanks to the Southeast Chicago residents who donated artifacts relating to the Memorial Day Massacre to the Southeast Chicago Historical Museum. Our gratitude in particular to the Borozan family – Gerry Jolly Borazan’s scrapbook forms the heart of this story. Thanks also to Mike Borozan for participating in the opening and closing videos and for donating family photographs. Many items relating to the Memorial Day Massacre were donated by late labor leader Ed Sadlowski, an aficionado of union history and one of the founders of the Southeast Chicago History Project. Bill Bork donated audiotapes of oral histories conducted with George Patterson, Emil Badornac, and Sam Evett for a master’s thesis from 1975 that were key to the storytelling. Museum Director Rod Sellers and his Museology students from Washington High School, located across the street from the Memorial Day Massacre site, conducted oral histories with Gerry Borozan and Mollie West. Rod Sellers also shot video of countless Memorial Day Massacre commemorations sponsored by Local 1033 of USW. Our gratitude to all.

SOURCES USED:

Anderson, Paul Y.

1937“Eyewitnesses Describe Killing of Steel Strikers by Police”. St. Louis Post-Dispatch. June 20, 1937.

Bork, William Hal

1975The Memorial Day “Massacre” of 1937: And its Significance in the Unionization of the Republic Steel Corporation. Master’s Thesis, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign

Brier, Stephen

2001“Labor, Politics, and Race: A Black Worker’s Life.” [A transcript of a 1937 WPA Interview with SWOC Organizer Hank Johnson]. Labor History, pgs. 416-421.

Burley, Dan

1937“Five Men Killed in Bloody Steel Strike”. Chicago Defender, pg. 1, June 5, 1937.

Chicago Daily Tribune

1937“4 Dead, 90 Hurt in Steel Riot: Police Repulse Mob Attack on S. Chicago Mill.” May 31, Pg. 1.

1937“85,000 Strike; Police Act.” May 27th. Pg. 1.

Chicago Defender

1937“Funeral for Slain Steel Worker Held: Man Killed in Memorial Day Massacre Called Martyr at Service.” Chicago Defender, July 3, 1937, Pg. 6.

Dennis, Michael

2010The Memorial Day Massacre and the Movement for Industrial Democracy. New York: Palgrave McMillan.

Flores, John H.

2018The Mexican Revolution in Chicago: Immigration Politics from the Early Twentieth Century to the Cold War. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Girdler, Tom M. (with Boyden Sparkes).

1943Bootstraps: The Autobiography of Tom M. Girdler. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Kollros, James

1998Creating a Steel Workers Union in the Calumet Region, 1933-45. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Illinois - Chicago.

LaFollette Commission

1938Hearings Before a Subcommittee of the Committee on Education and Labor United States Senate. Parts 14 and 15-D. June 30, July 1st and 2nd, and November 18, 1937. The Chicago Memorial Day Incident. Washington, DC: The Government Printing Office.

Leotta, Louis

1971“Girdler’s Republic” Cithara. Vol. 11. Pgs. 41-66.

Patterson, George

1970Interview with George Patterson conducted by Edward Sadlowski; Dec. 1970-1971. Roosevelt University Archives.

Powers, George

1973The Legend of Joe Cook. Booklet. Donated by Edward Sadlowski to the Southeast Chicago Historical Museum and the Chicago History Museum.

Quirke, Carol

2012Eyes on Labor: News Photography and America’s Working Class. Oxford University Press.

Rosales, Francisco A. and Daniel T. Simons

1975Chicano Steel Workers and Unions in the Midwest, 1919-1945. Aztlan, 6(2):267-275.

Schuyler, George S.

1937“Schuyler Visits Steel Centers in Ohio and Pennsylvania; Finds Race Workers Loyal to Companies.” Pittsburgh Courier, July 24th.

1937“Negro Workers Lead in Great Lakes Steel Strike.” Pittsburgh Courier, July 31st.

Sofchalk, Donald

1965“The Chicago Memorial Day Incident.” Labor History, Vol 6, Winter. Pgs. 3-43.

White, Ahmed

2016The Last Great Strike: Little Steel, The CIO and the Struggle for Labor Rights in New Deal America. Berkeley: University of California Press.